As a lawyer/writer, I have always been a supporter of other lawyers/writers, of which there are many. But retired Judge Anne Simon is particularly noteworthy for her place-passion.

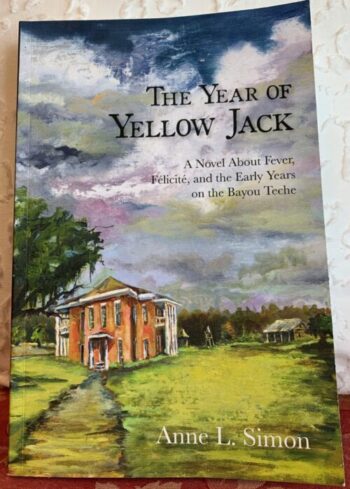

I recently picked up a copy of her latest novel, The Year of Yellow Jack, a fictionalized version of the true story of Félicité, a slave who helped save the fledgling town of New Iberia (then known as Nueva Iberia) from yellow fever in the mid-1800s.

The Year of Yellow Jack follows Hortense Duperier from her childhood in the fledgling town of New Iberia (when Félicité, Hortense’s grandmother’s slave, cared for her) into Hortense’s widowhood (by which time she had inherited Félicité as her own). The story depicts a close, almost maternal, bond between Hortense and Félicité as they face the town’s yellow fever invasion. Beyond the obvious challenge of blindly fighting a virus before modern medicine (a challenge which we can all now appreciate), Hortense and Félicité had to convince the frightened townspeople that Félicité’s methods (fever teas, rest, air, and water) were superior to the doctors’ typical treatment of bleeding (which involved a disgusting relationship with leeches). So successful were Félicité’s efforts in actual history that her life has been celebrated in New Iberia since her death in 1852.

The book is rich in historical facts, though some details remained vague. For instance, a semi-subplot touches on a point of uncertainty regarding whether Hortense actually owned Félicité, but the author did not further develop the issue. Apparently, it was resolved amicably, as the story ends with Félicité’s death by old age and burial in the Duperier family plot – a recognition unheard of for slaves in that era. Similarly, the novel frequently hints at Félicité’s tragic youth as a slave taken from St. Domingue (today’s Haiti) and sold away from her mother in New Orleans, but few sentences are devoted to the effect of this history on the story. Presumably this ties into Félicité’s history as a healer, but the connection was not robust. Nonetheless, these shortcomings (if they could be called that – and I’m not convinced they can be) are easily forgiven with the understanding that the book is primarily historical.

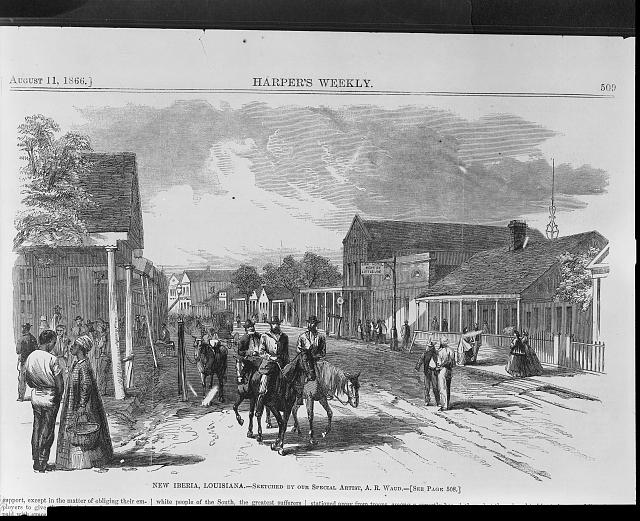

As with any fictionalized historical account, I was most excited to read a story set in a real place. New Iberia and St. Martinville are satisfyingly historical towns with a notable dedication to historic preservation.

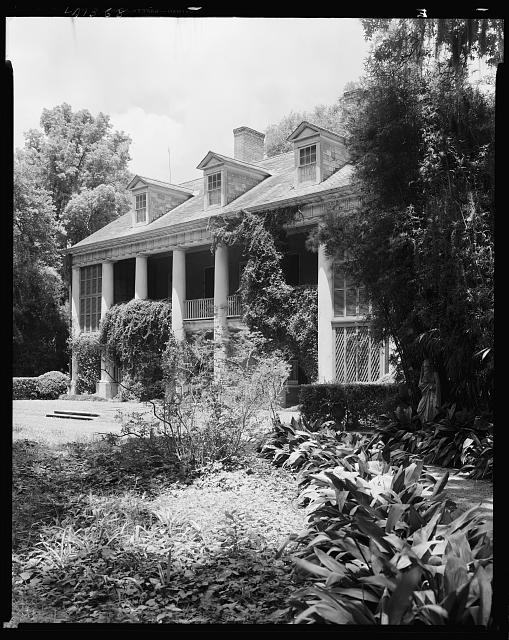

New Iberia is home to Shadows-on-the-Teche (c. 1831-34) owned by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Shadows is just down the Bayou Teche from the Duperier House (c. 1826), where the bulk of the novel is set. Interestingly, I had trouble finding a photograph of the Duperier House, until I discovered that the house is better known as the former Mount Carmel Academy. According to unverified internet sources, the Sisters of Mt. Carmel founded an educational institution for girls in 1876, decades after the events in the novel.

Another interesting internet discovery was the house’s purported connection to Louisiana’s infamous pirate, Jean Lafitte. [Aside: At the same time I picked up The Year of Yellow Jack from my local independent bookstore, Beausoleil Books, I also snapped up a copy of Jean Laffite Revealed by Ashley Oliphant and Beth Yarbough. Both of my new books were products of UL Press. Stay tuned for forthcoming thoughts on this next highly-anticipated read.]

Local legend maintains Lafitte’s connection to the Duperior House most likely due to the house’s underground tunnel that leads to the Bayou Teche. Ms. Simon mentioned the tunnels in the novel, and some of the characters feign a relationship with Lafitte. These details are all the more interesting because of their real existences. For an entertaining excuse to web-surf, check out one reporter’s effort to uncover the mystery of the Emma Window, which purports to be a window pane from the house upon which Emma Duperier etched her name with her engagement ring – the very same house built for Hortense in the novel (and presumably in actuality). Ms. Simon’s historical notations (including a Duperier family tree) did not identify any such person.

The Duperier House/former Mt. Carmel Academy is situated on, and many scenes traverse, the Bayou Teche, the hauntingly beautiful arterial bayou that winds from Port Barre to Morgan City. Bayou Teche’s headwaters are at Bayou Courtableau, another significant way-point in Louisiana’s history, and, of course, the scene in another book set in a real historical town.

I do love a good historical connection. Overall, I give The Year of Yellow Jack a Place-Ment Value of 8 for its depiction of an important historical figure in an authentic setting. Additional information on the later development of these places would have increased the book’s score, but I appreciate that the book is ultimately about Félicité–not her home. Kudos to Ms. Simon for sharing a wonderful story at such an appropriate time.